The hearty cheer came through the fog late Monday morning, startling Misti Arias and a handful of cows grazing nearby.

Arias, the general manager of the Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District was making her way down a fire road on Wright Hill Ranch, high above Highway 1, when a group of 15 or so hikers, coming up the road, shouted in unison, upon seeing her: “Thank you, Ag and Open Space!”

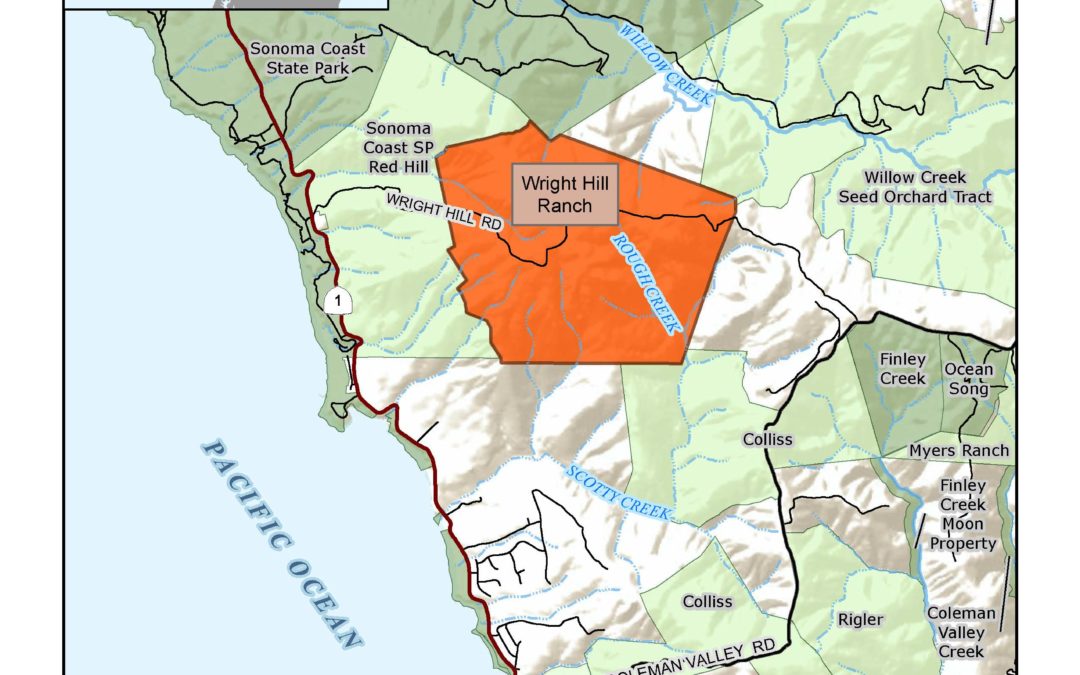

Those grateful hikers were employees of the county’s Regional Parks department. Their cheerful greeting captured the strong, highly productive working relationship shared by the agencies. Later this month, Regional Parks will take over this 1,236-acre coastal property, purchased by the taxpayer-supported open space district in 2007.

Wright Hill Regional Park and Open Space Preserve, as it will be known, won’t be fully operational for another 3 to 5 years, estimated Bert Whitaker, the county’s regional parks director, who joined Arias on Monday morning’s fog-shrouded walkabout.

Inhabited by Coastal Pomo tribes before it was purchased by the Wright family in 1863, the land was most recently owned by the Poff family, who sold it to the open space district 14 years ago for $5.6 million.

The district intended to transfer the land to California State Parks. That plan was abandoned when the Great Recession ushered in a budget crunch. As it has in other collaborations with the open space district, the county’s regional parks department stepped into the void.

“When it became clear that State Parks was not going to be able to work with Ag and Open Space for places like this property, for Carrington Ranch, for Calabazas Creek, that was when the parks in Sonoma County started rising to the occasion,” said Whitaker.

Over the last three decades, the open space district has transferred 7,871 acres of land to county parks — just over half of the department’s total acreage. Nearly 4,400 of those acres have been transferred in the last 3 years alone, leading to the creation of five new parks and open spaces.

The Wright Hill Ranch is different from most of his department’s other holdings, said Whitaker.

“It’s a large coastal preserve, not super accessible,” he noted. While he and Arias had reached the ranch via Wright Hill Road, a gravel byway 3.5 miles south of Jenner off Highway 1, the public will not have access to that route. The most efficient way to access the new preserve will be from the north. Hikers can park at the Pomo Canyon Environmental Campground, off Willow Creek Road, and hike up the Pomo Canyon Trail.

While that ascent is a bit “aggressive” for the first mile or so, Whitaker allowed, the payoff — after rising through thick, second generation redwood stands, then the grasslands above — is a dramatic view of the Pacific.

After emerging from a cathedral-like grove of bay and oak, Whitaker pointed south, extolling the “majestic perspectives” of Mount Tamalpais, some 60 miles distant. That he and Arias could barely make out the half dozen bovines grazing a hillside 50 yards away, so thick was the fog, made the moment only a little less dramatic.

Wright_Hill_Ranch_Transfer_location_map.pdf

Rising temperatures, and the ongoing, extreme drought, have made need for such acquisitions more urgent, said Arias.

While the climate is changing, “we can’t predict exactly what’s going to happen, where it’s going to get dry, where it’s going to get hot,” she said.

Scientists have emphasized to Arias and her staff the importance of protecting a wide variety of lands — “a diversity of microclimates, topographies, and habitats,” she said — to make sure wildlife have ample room for migration and adaptation, in response to warming temperatures, rising sea levels and other changes.

“The more available open land,” she said, “the better.”