by Connie White | Aug 24, 2021 | California Coastal Trail, News, Sonoma |

The hearty cheer came through the fog late Monday morning, startling Misti Arias and a handful of cows grazing nearby.

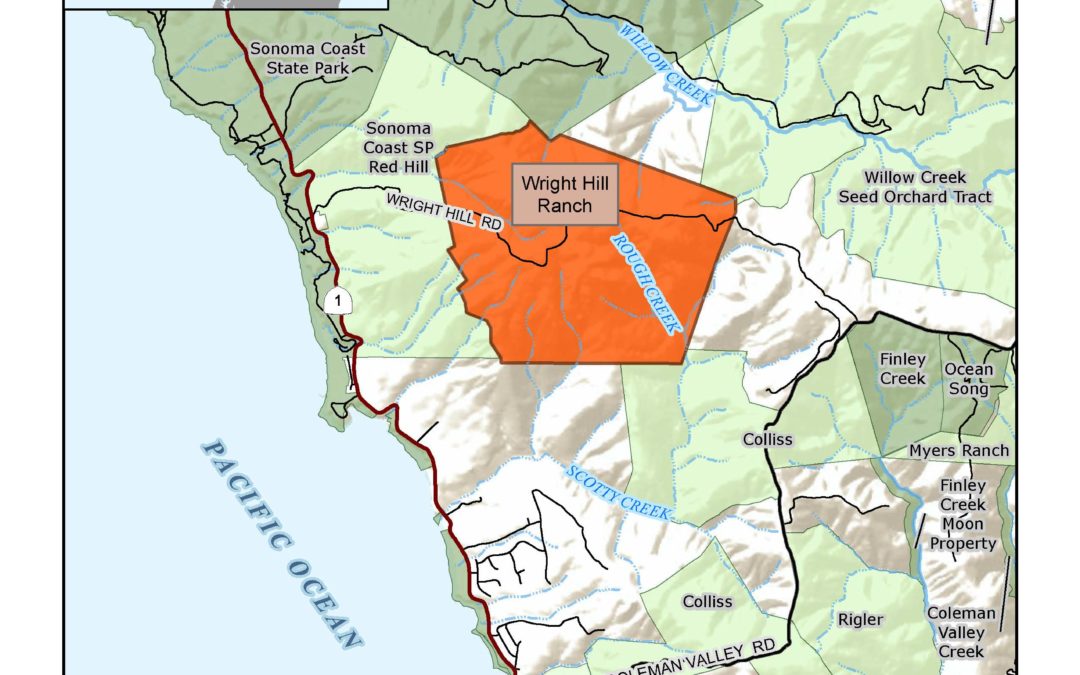

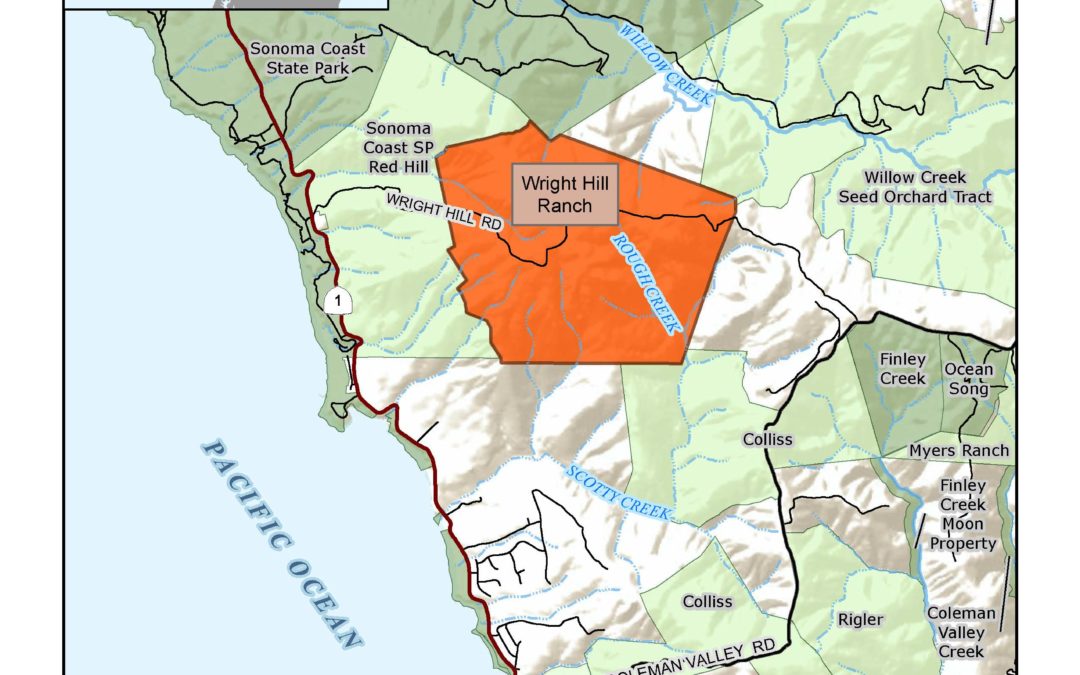

Arias, the general manager of the Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District was making her way down a fire road on Wright Hill Ranch, high above Highway 1, when a group of 15 or so hikers, coming up the road, shouted in unison, upon seeing her: “Thank you, Ag and Open Space!”

Those grateful hikers were employees of the county’s Regional Parks department. Their cheerful greeting captured the strong, highly productive working relationship shared by the agencies. Later this month, Regional Parks will take over this 1,236-acre coastal property, purchased by the taxpayer-supported open space district in 2007.

Wright Hill Regional Park and Open Space Preserve, as it will be known, won’t be fully operational for another 3 to 5 years, estimated Bert Whitaker, the county’s regional parks director, who joined Arias on Monday morning’s fog-shrouded walkabout.

Inhabited by Coastal Pomo tribes before it was purchased by the Wright family in 1863, the land was most recently owned by the Poff family, who sold it to the open space district 14 years ago for $5.6 million.

The district intended to transfer the land to California State Parks. That plan was abandoned when the Great Recession ushered in a budget crunch. As it has in other collaborations with the open space district, the county’s regional parks department stepped into the void.

“When it became clear that State Parks was not going to be able to work with Ag and Open Space for places like this property, for Carrington Ranch, for Calabazas Creek, that was when the parks in Sonoma County started rising to the occasion,” said Whitaker.

Over the last three decades, the open space district has transferred 7,871 acres of land to county parks — just over half of the department’s total acreage. Nearly 4,400 of those acres have been transferred in the last 3 years alone, leading to the creation of five new parks and open spaces.

The Wright Hill Ranch is different from most of his department’s other holdings, said Whitaker.

“It’s a large coastal preserve, not super accessible,” he noted. While he and Arias had reached the ranch via Wright Hill Road, a gravel byway 3.5 miles south of Jenner off Highway 1, the public will not have access to that route. The most efficient way to access the new preserve will be from the north. Hikers can park at the Pomo Canyon Environmental Campground, off Willow Creek Road, and hike up the Pomo Canyon Trail.

While that ascent is a bit “aggressive” for the first mile or so, Whitaker allowed, the payoff — after rising through thick, second generation redwood stands, then the grasslands above — is a dramatic view of the Pacific.

After emerging from a cathedral-like grove of bay and oak, Whitaker pointed south, extolling the “majestic perspectives” of Mount Tamalpais, some 60 miles distant. That he and Arias could barely make out the half dozen bovines grazing a hillside 50 yards away, so thick was the fog, made the moment only a little less dramatic.

Wright_Hill_Ranch_Transfer_location_map.pdf

Rising temperatures, and the ongoing, extreme drought, have made need for such acquisitions more urgent, said Arias.

While the climate is changing, “we can’t predict exactly what’s going to happen, where it’s going to get dry, where it’s going to get hot,” she said.

Scientists have emphasized to Arias and her staff the importance of protecting a wide variety of lands — “a diversity of microclimates, topographies, and habitats,” she said — to make sure wildlife have ample room for migration and adaptation, in response to warming temperatures, rising sea levels and other changes.

“The more available open land,” she said, “the better.”

by Connie White | May 5, 2021 | California Coastal Trail, Featured, News |

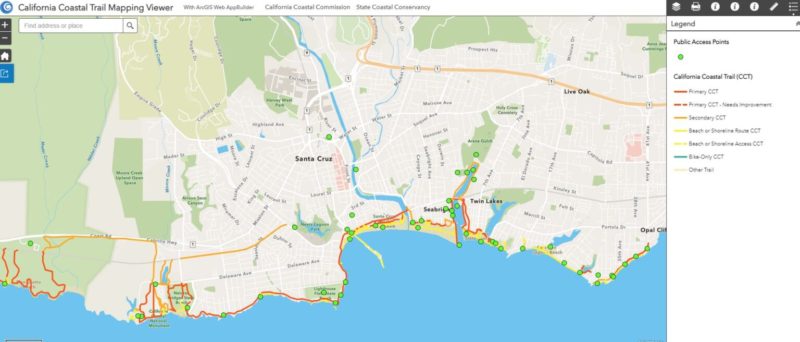

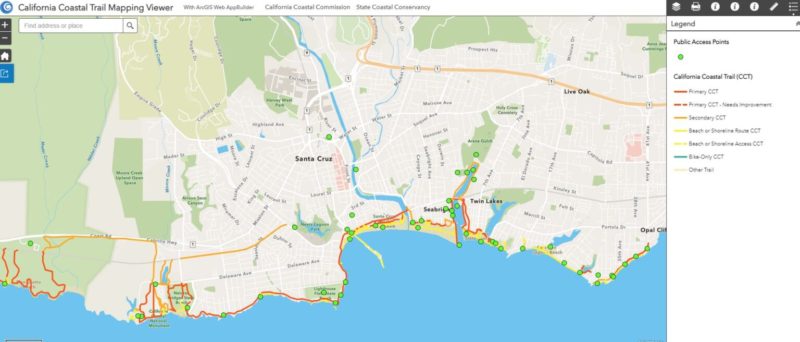

SAN FRANCISCO _ The Coastal Commission and Coastal Conservancy released a digital map that for the first time shows the existing sections of the California Coastal Trail, a three-year project that will be critical to completing the rest of the trail.

“What a milestone,” said Coastal Commission Executive Director Jack Ainsworth. “There are currently 875 miles of trail and now we can finally see exactly where they are, so we can eventually bridge those gaps and finish the trail.”

The California Coastal Trail, which has been in the planning since 1975, is a network of trails that will eventually allow the public to traverse the length of California’s 1,230-mile-long coast. The varied trail is not a single pathway but a collection of parallel threads and is about 70 percent complete. The trail takes participants through beaches, along blufftops and hillsides, on footpaths, sidewalks and separated bicycle paths maximizing scenic coastal views. Portions of the trail are accessible on foot, bicycle, wheelchair users and on horsebacks as well.

“The California Coastal Trail is one of the only flagship trails in the country that is accessible to almost everyone,” said Coastal Conservancy Executive Officer Sam Schuchat. “Many Californians have walked a segment or two without even realizing it! With this map, people can find trail segments easily, as well as public access points to get to the shore.”

Read More…

https://scc.ca.gov/2021/05/12/press-release-first-california-coastal-trail-map-will-help-complete-the-1230-mile-long-trail/?fbclid=IwAR2soR9z4t1qgV0YidpiuGAfd7_Ne3oLKxGdBmwMrtP-VmjoqQqJyCzLjKw

by Connie White | Dec 30, 2020 | California Coastal Trail, News, Sonoma |

Santa Rosa, CA – December 30, 2020 – The Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District (Ag + Open Space), a special district dedicated to protecting our working and natural lands forever, transferred ownership of a 335-acre coastal property to Sonoma County Regional Parks. This land, known as Carrington Coast Ranch, will eventually open to the public as a regional park and open space preserve just north of Salmon Creek.

“This project has been a long time in the making, so it is extraordinary to see the vision become reality and soon our community will be able to enjoy the rolling grasslands and beautiful vistas that make this property such a gem,” said Sonoma County 5th District Supervisor and Ag + Open Space Director Lynda Hopkins. “The conservation of our working and natural lands, including this new park and preserve, provides so many benefits to Sonoma County’s diverse communities. These include addressing climate change mitigation and adaptation, offering a place for all people to enjoy nature, and showcasing stunning scenic landscapes that define our region.”

Ag + Open Space purchased Carrington Coast Ranch in 2003 for $4.8 million. At the time, it was anticipated that the property would be transferred to and operated by California State Parks. However, due to budgetary constraints, State Parks was unable to accept title to the property. Ag + Open Space then began to work with Regional Parks on a potential park and open space preserve that would protect the ranch’s scenic and natural resources, while also providing for public recreation.

Carrington Coast Ranch hosts a diversity of natural habitats, including coastal prairie, coastal scrub, freshwater and saltwater wetlands, and tidal marsh. Several special-status species, such as the Townsend big-eared bat, California red-legged frog, and American badger have been identified on the property. The ranch is primarily open grassland, which affords spectacular views of the ocean, and sequesters carbon to help mitigate the effects of climate change, ensuring this area will adapt to sea level rise. The future park and open space preserve will provide a critical segment of the 1,200-mile California Coastal Trail and link to public lands to the north and south. (more…)

by Connie White | Jun 8, 2020 | California Coastal Trail, News |

Jun 6, 2020 Sonoma County Gazette

The primary goal of the California Coastal Act, approved by voters in 1976, is ensuring and providing for public access to the state’s shoreline and ocean.

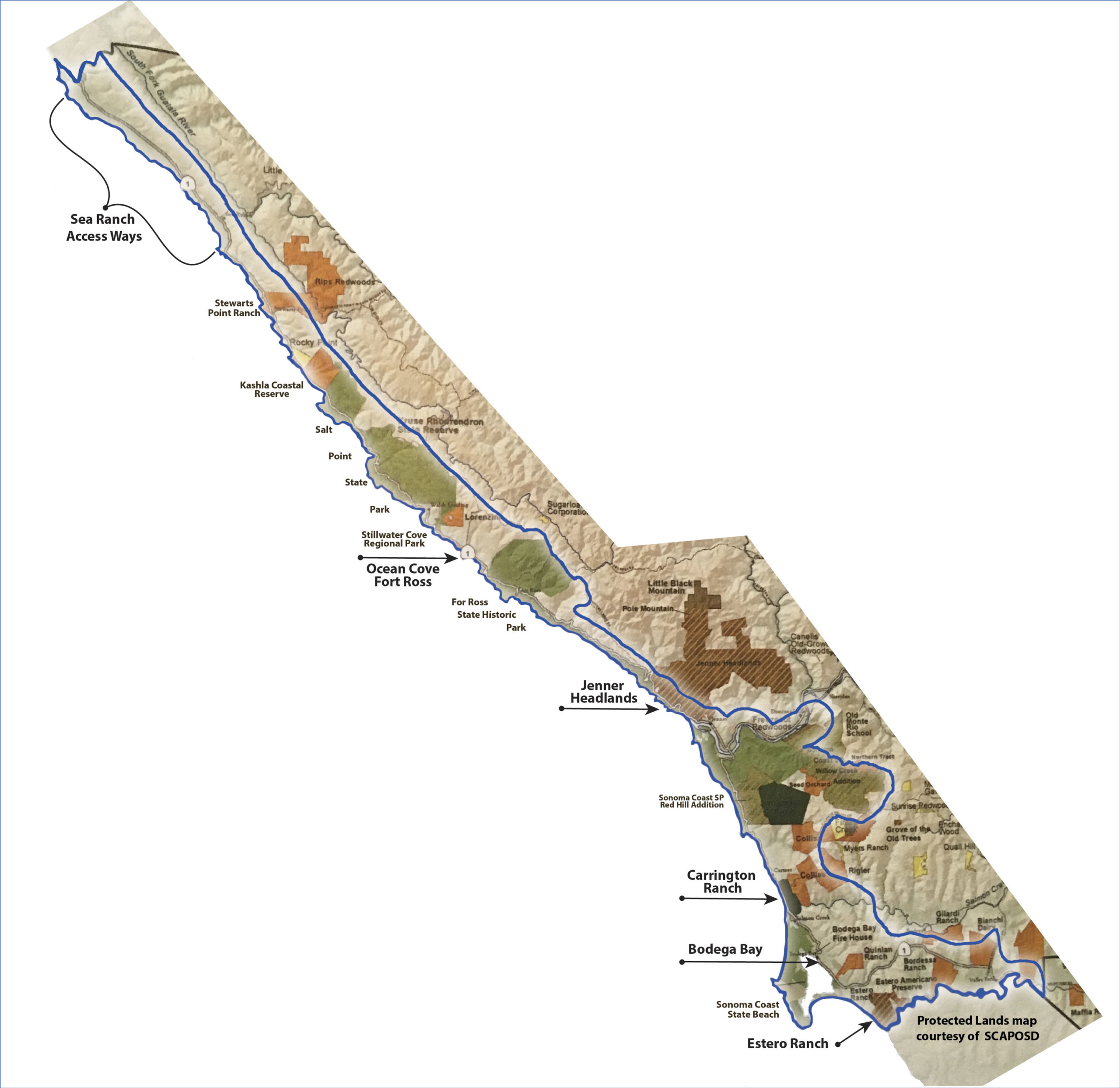

One of the dreams imbedded in that goal is the creation of a continuous trail along the coast from the Oregon border to Mexico, the California Coastal Trail.

It’s a breath-taking dream

The California Coastal Trail (CCT), when completed, will rival the famed Appalachian Trail in the eastern U.S. Roughly 1150 miles long, it would encompass 800 miles of coastline with twists and turns, swift rises with equally swift descents, braided together through beaches, bluffs, roadways, stairways and boardwalks. The CCT will provide a ribbon of protection for coastal access and preservation of coastal resources along the California Coast.

View from a section of the California Coastal Trail. Image: unofficialnetworks.com

The Coastal Act mandated that each coastal county and city, as part of developing their own Local Coastal Plan, include the planning and implementation of the California Coastal Trail through their jurisdictions.

Sonoma County has done so since the mid-1970’s, with considerable success. About two thirds of the county’s 65 miles of the California Coastal Trail has been completed, and planning for the remaining gaps is included in the current Draft Local Coastal Plan.

Enormous thanks are due to the local citizens’ groups, regional and state parks agencies, nonprofit organizations and public funding agencies, whose hard work has brought us this far.

One of the leading organizations in that effort was, and continues to be, Coastwalk/California Coastal Trail Association, the statewide advocacy group for the Coastal Trail, formed in 1980, and headquartered in Sebastopol.

Morgan (Mo)(very left) and Joce (Jo) second from right, interns at the CA coastal trail association, embarked on an expedition from Oregon to Mexico on the California Coastal Trail in the summer of 2016. Richard Nichols, former Executive Director of Coastwalk California and one of the 1996 CCT thru-hikers and his wife Brenda (second from left) met up with them along the trail and shared their favorite memories of Coastwalk in its heyday and told Jo an Mo about the founder of Coastwalk, Bill Kortum, who was a coastal access activist and environmentalist. Image: coastwalk.org

Read more on the MoJo Coastwalk at https://coastwalk.org/?s=richard+nichols

Richard Nichols, a former Coastwalk Executive Director, and author of “Hiking the California Coastal Trail”, was instrumental in raising CCT awareness, securing planning funds, coordinating coastal county progress and yearly hikes, and two Coastal Trail thru-hikes from Oregon to Mexico.

Una Glass, a Sebastopol City Council member and former Coastwalk Executive Director, pushed and prodded Coastal Trail development through the lean years following the 2008 recession.

Cea Higgins, Executive Director of Coastwalk/California Coastal Trail Association congratulating honoree and co-founder Lucy Kortum May 2018- Image: www.facebook.com/coastwalk/

The current Coastwalk Executive Director, Cea Higgins, is a coastal resident and avid surfer. Cea is working to address impacts on the CCT such as sea level rise, and create opportunities for underrepresented communities to experience the CCT. Cea is also working to solve the current financial and social problems of Coastal Trail implementation.The 2020 Coastwalk Guided Hikes have been canceled due to the pandemic, which is impacting the financial well-being of the organization. Coastwalk continues to work with state, county and nonprofit organizations to support California Coastal Trail implementation.

You can join or donate to support the organization here: https://coastwalk.org/join-donate/

There are remaining gaps to completing the Coastal Trail in Sonoma County.

Blufftop homes along the Sea Ranch property. On the Sea Ranch property, the public trail dead ends at a “private trail,” which is only accessible to Sea Ranch homeowners and their guests. Today, you can walk through the full length of Sea Ranch if you are staying in the community. Image: coastwalk.org

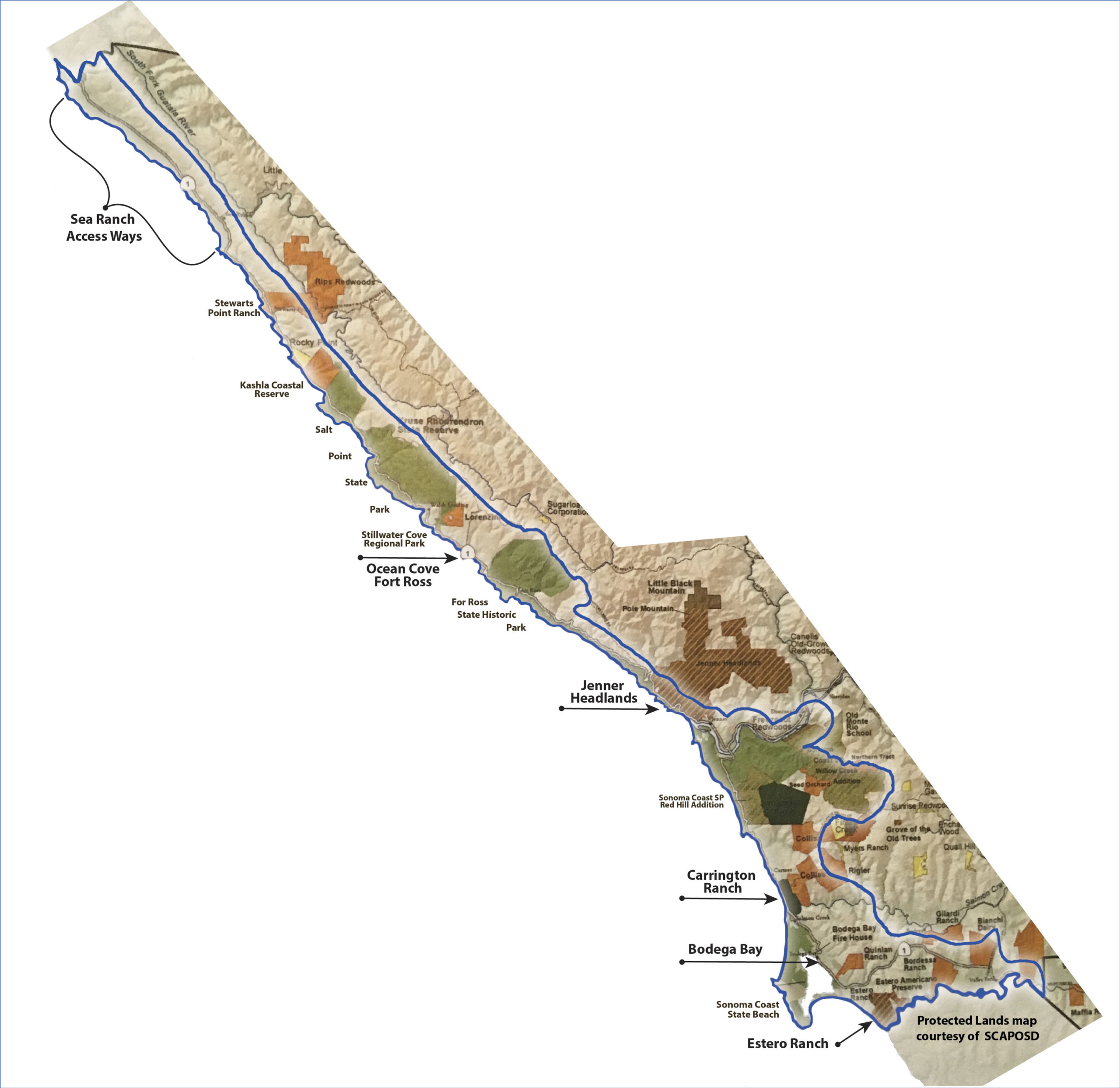

Negotiations with Sea Ranch in the early 1980’s provided five neighborhood trails and beach access, a three-mile-long bluff top trail for public use, and a 120-acre donation to create Gualala Point Regional Park. Completion of the Coastal Trail would require a through trail 12 miles long (see map) from Gualala Point Regional Park south to connect with the proposed Kashia Coastal Preserve and Stewarts Point Ranch trails. Building this trail would require a considerable change in stance from Sea Ranch, where homeowners are wary of losing their privacy to hikers.

Click on map to view large zoomable and downloadable version. remaining gaps to completing the Coastal Trail in Sonoma County.

Another difficult area to implement is the seven-mile-long Highway 1 segment through Ocean Cove and Fort Ross ( see map). Highway 1, in places, is narrow and winding, and in numerous locations property owners have built into the highway right-of-way, complicating any planning process.A concerted planning effort was undertaken here, but natural and manmade complexities stalled the effort.

For the foreseeable future, Highway 1 will continue to be the Coastal Trail.

The management plan for the Jenner Headlands property (see map) includes a 2.5 mile segment of the Coastal Trail. Enhancement of the property has been underway by the Wildlands Conservancy for a decade. Public parking and restrooms and 15 miles of trails have recently been opened. When completed, the Jenner Headlands CCT segment will run from Russian Gulch to Jenner and connect with the Russian River Trail inland.

Jenner Headlands view. Image: Sonomacounty.com

South of the Russian River, the Carrington property (see map), soon to be added to the County Regional Park system, will provide two miles of Coastal Trail east of Highway 1 from Coleman Valley Road to Salmon Creek.

A Bodega Bay Trails Plan implementation has been ongoing for more than a decade, with Coastal Trail segments built both south and north of Bodega Bay such as the Coastal Prairie Trail.

Estero Ranch is riparian to the Estero Americano which meanders through the northern boundary of the ranch for over two miles

The recent acquisition of the Estero Ranch (see map) and subsequent CCT implementation will connect with the southern boundary of Bodega Harbour and traverse to the county line at the Estero Americano. Currently, the Coastal Trail south from Bodega Bay is on Highway 1.

A most difficult gap remains: how to construct a trail through Bodega Bay that will be affordable and provide maximum public safety for all trail users. A vital entity in Coastal Trail maintenance and improvement is CalTrans, especially in difficult areas such as Bodega Bay and Ocean Cove-Fort Ross. They are an integral part of Coastal Trail implementation.

Fisherboats at Bodega Harbor. Image: Frank Schulenburg / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)

The dream of a continuous coastal trail has been actively pursued by hundreds of people and organizations for nearly fifty years. In reality, much has been accomplished but much work remains. The future will require the continued hard work of dedicated public agencies, nonprofits and coastal trail enthusiasts.

It’s a worthy, wonderful dream that, when finished, will provide beauty and enjoyment for future generations

by Connie White | Feb 26, 2020 | News, Sonoma |

BODEGA BAY – A hearty band of volunteers spent part of their weekend hauling chunks of boat wreckage up the side of a coastal bluff, completing a clean-up effort launched about a month ago when it became clear no one else planned to do anything about it.

The debris — splintered wood, twisted metal, pieces of Fiberglass hull, a tangle of wire and rope — was all that remained of a small boat that capsized in the surf near Pinnacle Gulch on Nov. 25, throwing a family of four in the ocean.

That family, rescued from the beach by helicopter and sent home to Sacramento, was technically responsible for removing the ruins of their watercraft.

But, as in other cases where boaters have walked away from crashed or grounded vessels on the Sonoma Coast, volunteers — led by well-known coastal steward Cea Higgins — picked up the slack.

“I wasn’t seeing anybody else stepping up to do it, and it was too much of a risk, with storms coming in,” said Higgins, executive director of Coastwalk/California Coastal Trail Association and a longtime officer with the local chapter of the Surfrider Foundation.

She pointed out a mass of snarled cords, mesh and other materials waiting to be cleared from the beach last week. “This kind of netting and rope is pretty scary for marine mammals and entanglement.”

It’s a case that reflects on a confusing, frustrating area of coastal policy — and more broadly, on a sizable problem with derelict and abandoned vessels throughout California waterways.

There are rules that dictate which area of government should hold jurisdiction over each forsaken boat — depending which side of the mean high tide line it’s on, for instance. But the rules apply only if someone cares to consider the matter in the first place, if the jurisdictional lines are clear and if there is money available for the job, a rarity.

“It’s super convoluted,” said state Fish and Wildlife Officer Mitch Goode, who works with the department’s Office of Spill Prevention and Response and has a lead role in state efforts to tackle the issue.

But there are hundreds of abandoned, sinking and nonseaworthy boats littering the Sacramento Delta, the extended reaches of the San Francisco Bay and all along the vast California coastline. They include three vessels that sank in Bodega Harbor years ago and yet remain, their owners in the wind or deceased.

The rusted steel hull of a fishing vessel driven up on South Salmon Creek Beach in 2016 also remains stranded in the surf line. Most of the hull is filled with sand.

“Anybody can become a fisherman, and if something bad happens, we’re all on the hook,” said self-styled “Coastodian” Richard James, a west Marin County environmental steward.

A Central Coast fisherman walked away from grounded vessels twice in 2012, months apart at the Point Reyes National Seashore and on the same Sonoma County beach near Pinnacle Gulch that was cleared Sunday of wreckage from November.

In the Point Reyes case, the National Park Service spent upwards of $80,000 demolishing and carting away a 43-foot commercial vessel owned by well-known fisherman Duncan MacLean, Supervisory Park Ranger John Eleby said. MacLean would soon ground another one in Bodega Bay, each time without insurance, Eleby and others said.

When MacLean grounded the 35-foot Sea Biscuit near Pinnacle Gulch and what Higgins calls Skimboarders’ Beach, volunteers were left with a mess of fuel-soaked debris far more toxic and troubling than the relatively small pile of sunbaked debris a group of 18 people tackled over the weekend.

“There’s no accountability,” James said, contending that owners can take their boats out uninsured and leave others holding the bag when they run into trouble.

In general, the process is clunky and inefficient when owners fail in their duty, leaving boats to break up and become environmental hazards, she said.

“It shouldn’t have to be that way. There should be processes in place. Because shipwrecks are a reality. We have treacherous beaches,” Higgins said.

Government agencies do not want to salvage wrecked boats unless it is part of their mandated responsibilities and they have funding for it, Goode said.

The U.S. Coast Guard is generally quick to arrange for removal of fuels and toxic substances from a stranded boat and might tow a vessel that’s deemed a hazard to navigation. But otherwise, boat salvage is not its function, officials said.

The Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, working with the Coast Guard and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s law enforcement arm, might pitch in to resolve a situation involving a grounded vessel that could harm sanctuary resources, but only if there are funds available, said MaryJane Schramm, sanctuary spokeswoman.

“Right now the ‘pot’ is empty,” she said in an email.

The California Coastal Commission, meanwhile, has responsibility for boats that come ashore below the mean high tide line, while the owner of whatever property lies above that line — often the county or the state — is supposed to bear the burden for vessels that land higher up shore.

The boat that capsized in November may fit that description. Photos taken at the time of the rescues show the overturned boat in the surf before it was broken up and the pieces tossed on the beach.

Higgins, worried that the styrofoam, rope and everything else would be swept back to sea, began collecting the fragments a few weeks later and stashing what she couldn’t carry up the cliff higher on the beach until king tides hit earlier this month and she knew she had to get it off the beach altogether.

“If I started saying, ‘It’s your job; you should do it,’ then it doesn’t yield the results I’m looking for, which is trying to minimize the impacts in the most expedient way possible,” she said.

County parks, which owns the beach, pitched in Saturday with personnel, a dump truck and other supplies, helping to leave the beach clean.

But Higgins, 56, concedes the process must be fixed so the environment isn’t paying the price for gaps in government responsibility.

“I’m not going to be here forever,” she said. “What happens when I’m not around? Who’s going to do this?”

You can reach Staff Writer Mary Callahan at 707-521-5249 or [email protected]. On Twitter @MaryCallahanB.